Insights

Does trusted ‘barometer’ mean a recession is imminent?

Oliver Sinnott

Oliver SinnottFixed Income Fund Manager

The recent stock market correction has largely been attributed to increasing concern about the health of the global economy. This fear has been amplified by a growing inversion of the US yield curve, a previously trusted harbinger of economic recession. “This time it’s different” is the typical refrain of recession deniers. So is it?

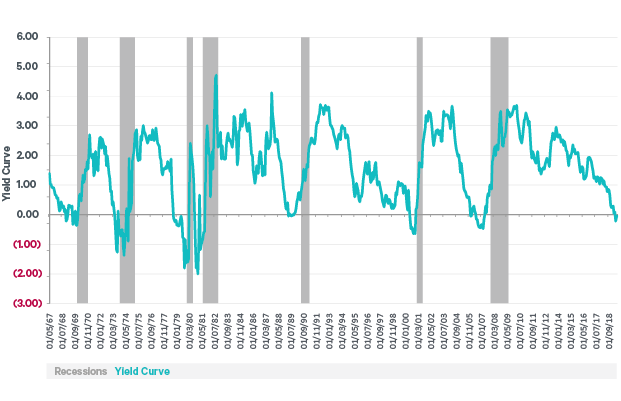

An inverted yield curve simply means that longer dated bonds yield less than shorter dated bonds. At the time of writing the US 10-year Treasury yields 0.37% less than 3-month Treasuries. Given that an inverted yield curve has preceded a remarkable seven out of the last seven recessions since the 1960s (see figure 1 below), one cannot lightly dismiss the possibility that it is doing so now.

Figure 1: The Yield Curve and Recessions

Source: Davy, Bloomberg, NBER. Data is monthly and as at 31/07/2019. Note this yield curve in this instance is the difference in yield between 10-year and 3-month US Treasuries.

Notwithstanding this formidable record, I believe there are compelling reasons why the current inverted yield curve signal may not have the same predictive power as those in prior cycles. The main reason is the role that central banks globally have played in artificially lowering the yield on long dated bonds.

Central bank policies have dramatically impacted bond pricing

In order to defeat the Global Financial Crisis, the European Debt Crisis and Secular Stagnation (anaemic growth and inflation) over the past decade, the world’s largest central banks introduced unorthodox monetary policies, including Quantitative Easing (QE), which have had a profound impact on bond market pricing.

QE in its most basic form is “printing” money to buy bonds. In theory this boosts activity by increasing money supply to the economy and lowering longer term borrowing costs (bond yields) for countries and companies.

The Curve is artificially Inverted

Central banks have been so successful at reducing longer term interest rate expectations through QE and other unorthodox policies that, all other things equal, we believe the 10-year US Treasury should yield at least 1.5% more than current levels. It is not an exact science, but we believe our estimate is conservative.

Obviously if the US 10-year yield was 1.5% higher, then it would yield more than 3 month Treasuries and the curve would no longer be inverted. With these policies here to stay (e.g. ECB look like they are going to embark on even more QE from September), we may have to live with more frequent yield curve inversions going forward, but hopefully without the same historical risk of recession.

Danger of a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy?

I should stress that even if the yield curve is artificially inverted and not as reliable as in the past at predicting recessions, its occurrence is not completely benign. Firstly, there is the risk of a self-fulfilling prophecy. As stated above, given an inverted yield curve’s formidable record at predicting recessions and all the media attention it is getting it may hurt business and investor confidence.

Secondly, it may also have real world implications by hurting banks’ profits. Traditionally banks earn a Net Interest Margin (NIM) by borrowing at the short end of the curve (e.g. by taking in deposits) and lending at longer maturities (e.g. mortgages). If NIM’s are squeezed (reducing the profitability of lending for banks) there is a risk banks could rein in lending, which might starve the economy of credit. We are monitoring this closely and, thankfully, so far in the US where the curve has inverted, ample credit continues to be flowing to the economy.

Global Resilience is being tested

Regardless of the US yield curve inversion, there is no doubt that global growth is slowing and risks to the cycle have increased in recent months. We believe the main risk is the US/China trade war which has intensified and led to broad weakness in the global manufacturing sector and restrained business investment.

Encouragingly, the global economy is showing resilience so far. While the manufacturing sector is suffering, the service sector has been more robust. The labour market and importantly the consumer is holding up well almost everywhere, monetary policy is supportive with most central banks following the Fed’s lead and turning more dovish this year, and there are increasing signs that governments are about to open the purse strings to support growth. Examples of this include the US, which is already pursuing expansionary fiscal policy, the UK where Boris Johnson’s government may announce fiscal stimulus in the Autumn, and Germany, which is reported to be readying a €50 billion package.

The Art of the Deal (or no Deal)?

The good news is that cycles typically end when there is a recession in the US, and currently it is the standout economy in the developed world. We find it difficult to believe that President Trump won’t want a strong economy heading into next year’s elections, and therefore we believe he would like to do a deal, or at least come to some sort of truce with China if the trade war increasingly hurts US growth.

However, a trade war between the world’s two biggest economies is likely to have many unintended consequences, and the more it intensifies, and the longer it lasts, the riskier it becomes for the global economy and financial markets. As such, this is an opportune time for investors to reflect on whether their portfolios are appropriately diversified and consistent with their objectives and risk tolerance.

Contact a member of our team to find out more

+353 1 614 8874

Please click here for Market Data and additional important information.